Thomas Mann had a short but memorable connection to Lithuania. Five years after the publication of his novel The Magic Mountain, in August 1929, he, his wife Katia Pringsheim-Mann and their two children arrived in Nida, an archaic fishing village on the Curonian Spit, a peninsula surrounded by the Baltic Sea, Curonian Lagoon, pine forests and sand dunes. The family stayed at Hermann Blode’s, a guest house with colorful memories of German expressionist painters. During their six-day stay, the Manns came up with the idea to build a summer house in Nida. A small house in the local architectural style was built in less than a year on the high ground known as Uošvė Hill. On July 16, 1930, the Mann family opened the doors of their new summer house. This time, the writer came to the fishing village as a Nobel Prize laureate. Part of the prize money was used to cover the construction costs of the residence.

In the summers of 1930-1932, in Nida, Thomas Mann worked on his largest work – the novel Joseph and His Brothers, based on the Old Testament. However, he was not meant to enjoy the peace he had dreamed of for long. In September 1930, the National Socialists became the second largest party in the German parliament. The approach of fascism could also be felt in Nida. Members of the Hitler Youth paraded in the village. One time a burnt copy of the Budenbrooks came flying into the yard of the writer’s residence. Then someone broke the windows of the house. The ghost of a new war was just around the corner… The family left in a hurry and relocated to Switzerland.

Today, the summer residence of the Manns in Nida houses a memorial museum where the Thomas Mann Cultural Centre has been operating since 1995 and the International Thomas Mann Festival has been held annually since 1997. In over two decades, the festival has become a meeting place for Lithuanian and foreign intellectuals and artists, a venue where the challenges of the contemporary world are discussed, seminars organized, and high-level classical music concerts held. Thomas Mann’s summer house in Nida, which will soon celebrate its 100th anniversary, is a magnet that opens up to the horizon…

***

Thomas Mann began writing a satirical short story for a magazine on the eve of World War I but stopped working because of the war. The Magic Mountain was not completed until 12 years later. In his essay The Making of The Magic Mountain, published in The Atlantic in 1953, Mann writes: “It is possible for a work to have its own will and purpose, perhaps a far more ambitious one than the author’s — and it is good that this should be so. For the ambition should not be a personal one; it must not come before the work itself. The work must bring it forth and compel the task to completion.” Having called The Magic Mountain his lifework, the closest thing to his own personality, Mann said that this novel most closely embodies “the leitmotif, the magic formula which works both ways, and links the past with the future, the future with the past.”

The eighty-year-old Polish director Krystian Lupa is one of the last active European theatre Mohicans of the eldest generation. Previously inspired by the oeuvre of Thomas Bernhard, the director has used its theatrical potential to the fullest. In his most recent productions (Capri: the Island of Fugitives (2019), Austerlitz (2020), Imagine (2023), and The Emigrants (2024)), Lupa looks for a similar magical formula, “which links the past with the future” as Mann, and the credo of his work is akin to Mann’s idea of the creative process as a journey that is subject to the “will and the purpose” of the work itself. In Lupa’s performances, the memory of the 20th century is intertwined with the traces of humanity’s historical mistakes in the present, and it is only one’s inner world that becomes one’s refuge from the apocalyptic worldview of the future Walter Benjamin spoke of through the metaphor of the Angel of History: “His eyes are wide, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”

According to Mann, “it is almost impossible to discuss The Magic Mountain without thinking of the links which connect it with other works; backwards in time to Buddenbrooks and to Death in Venice; forwards to the Joseph novels.” The Buddenbrooks and Death in Venice, two of Mann’s most powerful early works. Both of their contexts were crucial for Lupa in shaping the directorial solution of The Magic Mountain.

The Buddenbrooks – the debut novel of Thomas Mann, written by him in his twenties, divulged his family’s secrets and posed a creative challenge to his older brother Heinrich, who had already received their father’s blessing to become a writer. It is to him that the author of The Buddenbrooks addresses the phrase of one of the novel’s younger characters, “I have become who I am (…) because I didn’t want to be like you”, which started a bitter creative dispute between the two brothers that lasted for years. It began during the First World War, when Thomas Mann, in an open polemic with his brother, wrote his controversial opus “Reflections of a Non-Political Man.” And it was continued in the images of the characters of The Magic Mountain.

In Death in Venice Thomas Mann exposed himself for the first time, revealing his sexual identity previously hidden behind marriage and fatherhood. According to Lupa, here “Mann portrays an old hero who has already made all the major decisions in his life, something Mann wasn’t at the time, because he was still a young man who could seemingly change something. While Death in Venice is a kind of anticipation, The Magic Mountain is a return to a moment when decisions could still be made.” It is this circumstance that also entered the book Mann began writing after Death in Venice – The Magic Mountain – and enabled him to model a close and ever-changing personal relationship with Hans Castorp, the protagonist of The Magic Mountain.

In Lupa’s opinion, The Magic Mountain is not a typical Bildungsroman in the tradition of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (Wilhelm MeistersLehrjahre,1796), because it does not educate the young man Hans Castorp, but, on the contrary, introduces him into inner chaos. According to Lupa, the same chaos also engulfs the author of The Magic Mountain, for “how can one write about chaos without entering chaos? And the more you enter it, the more you find yourself in your own chaos. Even though you write about it with a scalpel, like Thomas Mann…” Out of this chaos a mysterious and unpredictable journey into your inner self is born.

Journey is the key word when talking about Lupa’s creative method. It is a journey into the unknown based on exploration and collective work trying to penetrate the mysteries of a work of literature and the human psyche. In the case of The Magic Mountain, it is first and foremost a journey into the personality of Mann himself and his secret relationship with the character of Hans Castorp. For Lupa, it is important that Mann did not walk the path of his hero, but he wanted to walk it, so he had to design it for himself based on other people’s experiences and literary sources. This journey of writing for Mann became more real than his real family life, concealing his furtive passions.

The journey is also related to the fact that the novel was written before and after World War I. The war was a pivotal fact that changed Thomas Mann and his perspective on writing, and shaped the narrator’s relationship with his protagonist, as we see it in The Magic Mountain. Lupa believes that Mann as a person was much more dramatic and genuine after the war than he was before it. “The first part of The Magic Mountain was written before the war, by a man who had a completely different attitude towards everything: the impending war as well as the situation of Germany in the war. At that time Mann was still a 19th century German man, a nationalist, who justified the war and believed in the victory of his country. Unlike his brother Heinrich Mann, who condemned the war from the start. The humiliation of losing the war and the defeat of his nation deeply affected Thomas Mann, it seemed like the defeat of an entire era. And then an astonishing thing happened. He returned to The Magic Mountain as a completely different man. A man who was looking at what he had believed before from a great distance. The war had profoundly changed the concept of humanity and man. I would very much like to build on this dual perspective in my performance.”

When presenting his idea of The Magic Mountain, Krystian Lupa said that it was important for him “to convey in the play what The Magic Mountain meant to Thomas Mann himself and to the world in which it was created. As well as to reflect the circumstances of the play’s creation.” Lupa thinks the performance should have two acts. In the first act, we would see the world before the war, and in the second – the world already affected by the trauma of the war. Through the dramaturgical contrast of the two acts, the director aims to show the evolution of the world from the 19th century manners and the optimistic faith in human reason and new technological discoveries of the early 20th century, to the collapse of all illusions and the deep anxiety about the future of the world…

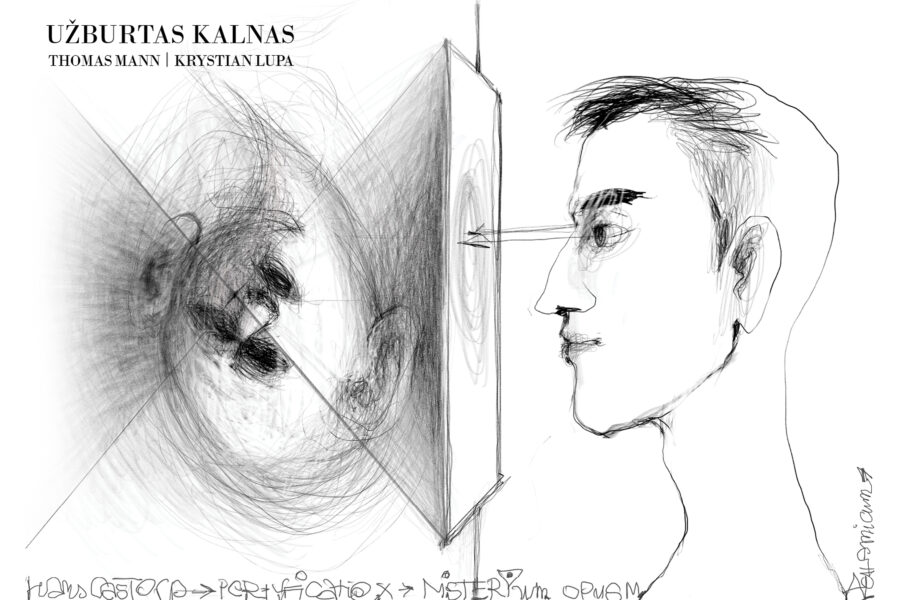

“Is The Magic Mountain the question or the answer? Does Thomas Mann reveal the secrets of his life or create them? Who is the narrator in The Magic Mountain?” With these questions, Lupa invited the actors to embark on a challenging creative journey and offered them the chance to become creative partners. Lupa began rehearsals without a script, nor did he immediately assign all the roles to the actors. He knew who would play a few main roles and had a directorial idea, which he expressed in a sketch of the stage design. “The most interesting things in The Magic Mountain are not fixed, but in a constant state of flow. What happens to the protagonist is not entirely real or tangible. We can say that The Magic Mountain is a dream mountain, where the personality is blurred. That’s why I can’t imagine a play in which the actors are tied to specific roles. They should be free to move between them.” Said the director during the first rehearsal.

In his interpretation of The Magic Mountain, Lupa draws on Mann’s frequent use of the pronoun “we”, which gave him the idea of a “collective narrator”. In the performance, such a collective narrator will be embodied by different characters who become narrators at certain points in the performance. When referring to the “collective narrator”, Lupa uses the metaphor of painting. Each individual character, with the identity and thoughts of the actor, is like a “brush”. “On the stage, three brushes paint while seventeen wait for their turn… Everyone is hungry for life and an experience similar to the one Mann gave his hero. So, on the one hand, Hans Castorp is a creation of Mann’s imagination and self-identification and on the other – the self-identification of the actor as a way of being himself. It brings about a craving to say something personal…” From this common craving, the narrator of The Magic Mountain should be born as a man of our time.

The idea of turning different characters into companions and narrators of Hans Castorp’s dreamlike journey resulted from the process of creating the performance itself. “I need your watching eyes so that I can pull something out of my subconscious against their wall, as if in an execution…” Lupa told the actors, admitting that he draws inspiration for his ideas from the actors’ work during rehearsals. In the same way, Hans Castorp himself needs the eyes of other actors looking at him for inspiration, because only through his relationships with others can he shape himself as a person.

Krystian Lupa’s journey has one peculiar feature: he delves deeply into what lies beyond the words, written or spoken. Because “the deepest human experiences cannot be expressed in language. When we try to express them in this way, we inevitably become liars. That is why we need to look for another, fundamental language.”Lupa calls it the “language of the dog”, which is “closest to what I experience”. The encounter with the literary oeuvre of W.G. Sebald (on which Lupa has based two plays, Austerlitz (Jaunimo Teatras, 2020) and The Emigrants (Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe, 2024), has inspired a further search for such a language, linking deep universal experiences with events from one’s personal life that are not talked about. “Sebald’s reader must read not what he writes, but what he is silent about. Because what I say is not essential. What is not said is what really matters. It takes creative effort to read it. We can move this way of writing to the theatre and invite the spectator to become a co-creator – to radically take his own path while reading my silence as an author…”

Lupa reads Thomas Mann with the experience of Sebald’s interpretation, and this is what determines his perspective on The Magic Mountain. He notices the similarities between the two very different writers. In Mann’s case, this is revealed through the slightly ironic tone of The Magic Mountain, behind which lies everything the writer is silent about. As readers, we need to work to understand this silence. That special silence that connects man’s inner world with the mysterious order of the universe, which man himself destroys in the apocalyptic chaos of the world.

Just as Mann delicately manipulates the reader through the frequent use of “we”, Lupa seeks to turn the spectator into a co-traveler in a shared journey into the unknown. “Until finally, in the last chapter of the novel, “we” are the lost travelers, like ghosts swirling around you, poor Castorp, who lies alone on the battlefield… When I read that, the “we” made me burst into tears. And where am I, Thomas Mann, at this moment?”asks Krystian Lupa. And where are we, the spectators of The Magic Mountain?

***

The Magic Mountain is the third production by Krystian Lupa in Lithuanian theatre. We have worked on all of them together. The authors are different – Thomas Bernhard, W. G. Sebald, Thomas Mann. From today’s perspective, all these works seem obviously connected. They have given the Lithuanian theatre new and unique creative experiences and insights into the human being. Each performance – Heroes’ Square by Thomas Bernhard, Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald, and The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann – was a new challenge and creative inspiration for Lupa himself. From Bernhard, with whose work he is well familiar to the still unexplored literary continents of Sebald and Mann. In essence, it has been one common journey that has inspired its participants to search for new ways of theatrical narration and ask fundamental questions about the human being and the mission of theatre in today’s world.

Audronis Liuga